The evolution of Minnesota Wheat’s publications over the past 40 years mirrors technological advances across the media landscape. The organization thrived by adapting with the times while always staying consistent with its mission to deliver timely information to producers across the Northern Plains.

In the early 1980s, Kris Bergman (née Versdahl) served as managing editor of the Minnesota Association of Wheat Growers’ (MAWG) first publication, which a decade later became Prairie Grains. Bergman, who started out as an executive secretary before transitioning to communications, laughed recalling how the magazine was produced cut-and-paste style, using linetype and IMB Memory typewriters. Printing the mailing list alone could take an entire day. And good luck finding stock photos; there were none in those salad days.

“It was an interesting time – so archaic,” Bergman said during a phone interview from her home in Montana. “It was fun to see the magazine grow and change.”

Minnesota Wheat wasn’t behind the times. Far from it. By the mid-1980s, the Red Lake Falls, Minn.-based organization began using Adobe PageMaker, a desktop publishing computer program that was a precursor to Microsoft Windows. In the early 1990s, thanks to Minnesota Wheat’s partnership with the University of Minnesota, the organization received access to agriculture via research via the underground World Wide Web. Now, in the mid-2020s, Prairie Grains can be read online from our phones, a concept the original editorial team could’ve hardly imagined back in the 1980s.

“We were lucky to be part of (the internet) right from the outset,” Bergman said. “I loved all the technology. It was fascinating. It was kind of gradual; I mean, nobody really understood this whole digital revolution. Now, things happen so fast, and I’m overwhelmed by it.”

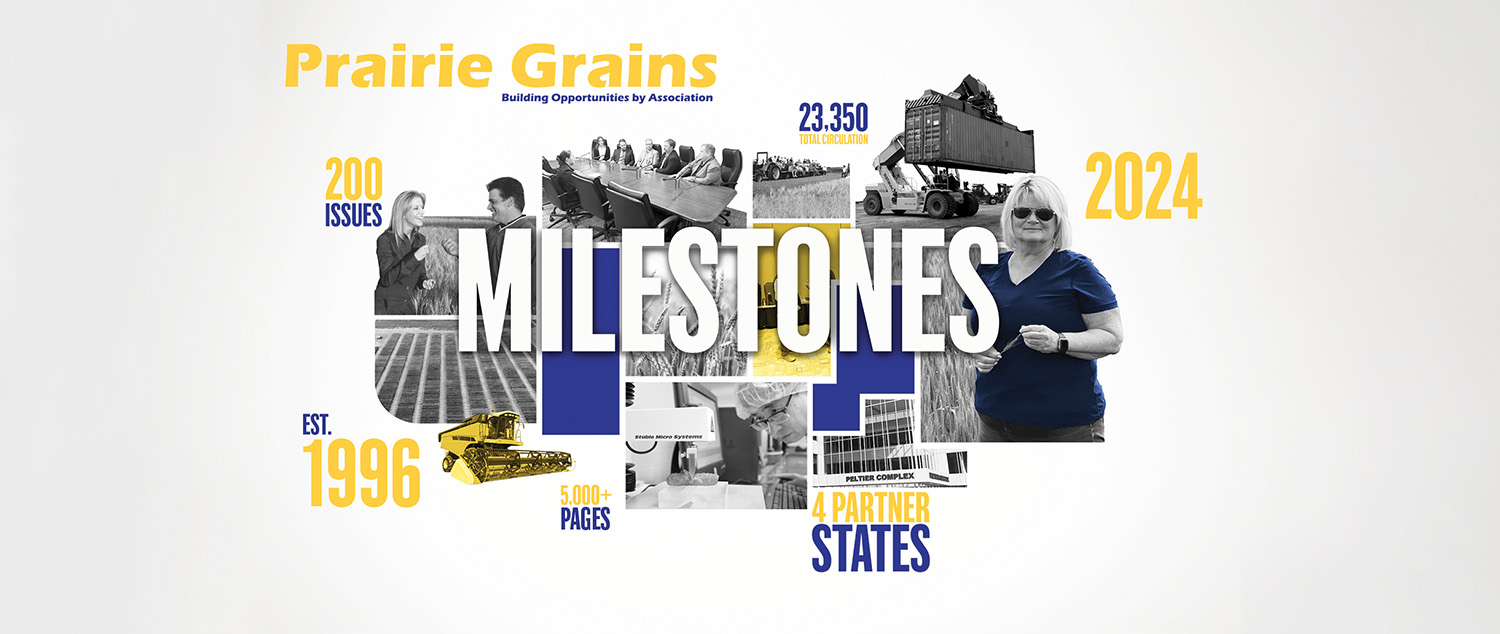

Bergman and former Minnesota Association of Wheat Growers (MAWG) Executive Director Dave “Torgy” Torgerson were more amazed than overwhelmed when told that Prairie Grains is celebrating its 200th edition across nearly 30 years of production.

“Has it really been that long?” Torgerson asked.

It has.

Wheat’s wordsmith

Minnesota Wheat’s debut publication was a tabloid-style newsletter, titled simply “Minnesota Wheat.” About 8-10 issues were published each year, averaging about a dozen pages. Editorial coverage focused on wheat checkoff projects, foreign market development efforts and MAWG’s legislative activity. Marv Zutz, executive director of Minnesota Barley, remembered huddling in the office to edit stories in the hours before publication deadline.

“Everybody would help proofread.” Zutz said. “Guys with accounting backgrounds don’t like that stuff, but it was always a team effort.”

By the end of the 1980s, MAWG’s board realized it was missing an opportunity by not featuring its farming neighbors in North Dakota and South Dakota. Directors decided to create a new glossy magazine, called Spring Wheat.

“Torgy and the board of directors at the time were visionaries for embracing North Dakota and surrounding states by trying to find a way to streamline and work together better,” Bergman said.

Everyone involved in the Spring Wheat/Prairie Grains’ operation agreed that journalist Tracy Sayler was the key ingredient in transforming the magazine into a respected source of agriculture information during the 1990s and into the 21st century.

“Tracy came up with the name Prairie Grains and he guided that thing,” said Tim Dufault, who also helped sell magazine ads and is current chair of the Minnesota Wheat Research & Promotion Council and past MAWG president. “It was very well done from the beginning.”

When Spring Wheat transitioned to Prairie Grains in the mid-1990s, Sayler served as editor and penned a back-page column called “Prairie Ramblings.”

“He was our wordsmith,” Zutz said. “He was one of those guys who loved English.”

Under Sayler’s editorial leadership, the magazine continued focusing on research, international marketing and was crucial in relaying news about the Scab breakout.

“Tracy was really good at taking scientific information from wheat researchers and putting it into a story that growers could read easily,” Torgerson said.

Sayler’s death in 2007 left a huge void at the magazine.

“After Tracy passed, it was hard to keep it going,” Torgerson said. “The magazine is only as good as the writers and designers, and it’s hard. There’s not that many ag communicators around.”

Still, Prairie Grains persevered by using writers and photographers from across the region and tapping into Prairie Ag Communications. In late 2020, MAWG contracted with Ag Management Solutions to help oversee the regional magazine, which now reaches as far west as Montana. In a sign of the times, Prairie Grains’ first issues of 2021 were compiled remotely during the height of the pandemic.

“The content has changed a bit,” said Torgerson, who remains a MAWG member, “but, boy, Prairie Grains is still always fun to read, and I think the coverage of all four states has only improved.”

Bergman credited Prairie Grains readers and Minnesota Wheat’s leadership for reaching the 200-issue milestone.

“The readers have always been engaged and interested,” she said. “And I give kudos to the people who served on the (MAWG) board over those years. It was their amazing leadership that helped Prairie Grains evolve.”